NPR would not call it plagiarism when Melania Trump’s speech to the Republican convention took passages from Michelle Obama. But there was a revealing moment when its people defended this policy online.

Hey, readers! This will take some explanation but if you bear with me, I promise: by the time you get to point 9 it will be worth it.

1. On the morning after Melania Trump’s speech, Standards & Practices Editor Mark Memmott published this note about NPR’s policy. The message: we can’t call it plagiarism unless it’s intentional.

On The Definition Of Plagiarism

Because it’s in the news today, here’s a reminder about how we have defined the word “plagiarism”:

“Taking someone else’s work and intentionally presenting it as if it is your own.”

Note the word “intentionally.”

We can talk about phrases that are “word-for-word” or that “mirror each other.” It’s fine to say there’s a “plagiarism issue” or that the speech last night raised questions about whether some parts were plagiarized. But we don’t know at this time whether anything was done “intentionally.” So don’t declare that there’s been some plagiarism.

2. You can see the NPR policy at work in the many reports it prepared about the Melania Trump speech. They all avoided the word “plagiarized.”

“Melania Trump’s Monday Speech Mirrors Michelle Obama’s…” (Link.) “…language in Melania Trump’s Monday night convention speech that was near-identical to a similar speech Michelle Obama delivered in 2008.” (Link.) “Melania Trump Echoes Michelle Obama.” (Link.)

Even after Trump staffer Meredith McIver took responsibility for using Michelle Obama’s words without credit, NPR would not call it plagiarism. (Link) Why? Because she didn’t mean it.

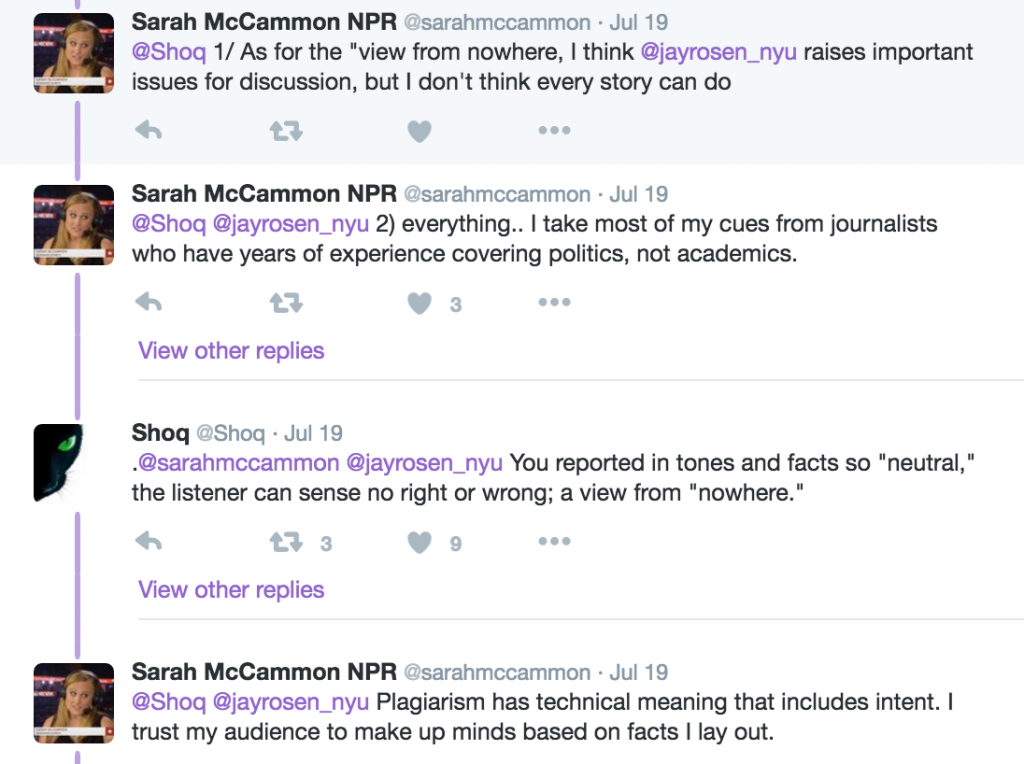

3. I came across Memmott’s note because I was mentioned on Twitter by an NPR reporter, Sarah McCammon, as she was being taken to task by a user named Shoq, who often comments on media issues. Here is some of that exchange:

4. This brought into the discussion my NYU colleague Clay Shirky. He had the following exchange with Sarah McCammon. (Link.)

Shirky: “Sarah, that’s wrong. When professors look for plagiarism, we look for copying without attribution, period.”

McCammon: “I’m aware. My husband is a professor. Different standards for different situations/fields.”

Shirky: “Are you are walking back your ‘technical’ excuse? And saying NPR’s standard is just not to use the word?”

McCammon: “Uh, not an excuse. Not walking anything back. Again, I refer you to our policy. NPR’s guidelines are different than many academic institutions, which understandably may have a lower threshold.”

Remember those words: “lower threshhold.”

5. Shirky’s point can be seen in this passage from NYU’s ethics handbook for journalism students:

Cardinal Sins

Plagiarism: Journalists earn their living with words, and plagiarism — using someone else’s words as if they were your own — is, simply stated, stealing.

Nothing about intent. This is from the Harvard College Writing Program:

In academic writing, it is considered plagiarism to draw any idea or any language from someone else without adequately crediting that source in your paper. It doesn’t matter whether the source is a published author, another student, a Web site without clear authorship, a Web site that sells academic papers, or any other person: Taking credit for anyone else’s work is stealing, and it is unacceptable in all academic situations, whether you do it intentionally or by accident.

My italics. This one is from Oxford University’s guide for students: (My italics.)

Plagiarism is presenting someone else’s work or ideas as your own, with or without their consent, by incorporating it into your work without full acknowledgement. All published and unpublished material, whether in manuscript, printed or electronic form, is covered under this definition. Plagiarism may be intentional or reckless, or unintentional. Under the regulations for examinations, intentional or reckless plagiarism is a disciplinary offence.

6. These were Sarah McCammon’s main points as she responded to the many people on Twitter who were puzzled by NPR’s refusal to call what Melania Trump did “plagiarism.”

* Our guidelines say it has to be intentional. I have to follow them. (Link.)

* I can’t see into Melania’s mind. I have no way to judge intent. (Link.)

* I present facts and trust listeners to make up their own minds. (Link.)

* What academics say isn’t relevant. My reference point is other journalists. (Link.)

7. Other journalists? Well, the Washington Post had no trouble calling it plagiarism: Why it became almost impossible for the Trumps to insist Melania’s plagiarism was coincidence. Do they have lower standards than NPR? (Another example.) And it wasn’t just headlines: (All bolding by me.)

Memo to all remaining 2016 convention speakers, whether you’re a Republican or a Democrat: You are officially on notice. The words you say will be researched by reporters to determine whether they have ever been said before, in the same order in which you are saying them now.

This is the consequence of Melania Trump using plagiarized sections of Michelle Obama’s 2008 convention speech in an address to the Republican National Convention on Monday. Journalists now have a new game to play when speakers take the stage: “Spot the Source.”

Would the New York Times be one of the news organizations from which Sarah McCammon takes her cues? Nope.

“My name is Meredith McIver and I’m an in-house staff writer at the Trump Organization,” began an extraordinary statement she released Wednesday morning in which she took the blame for the disastrous plagiarism of Michelle Obama in Melania Trump’s prime-time speech Monday at the Republican National Convention.

CNN, maybe? Alas, no: “Donald Trump’s campaign finally moved Wednesday to shut down the distracting controversy over Melania Trump’s plagiarized speech by identifying the writer who worked on the speech.” Los Angles Times: same deal. “The Trump campaign released a statement Wednesday – ‘to whom it may concern’ – ascribing the plagiarized passages in Melania Trump’s convention speech to a scribe working for Donald Trump’s corporate operation.”

8. The point is: if NPR wanted to call a spade a spade it had a clear warrant for doing so— from academic sources, from journalism peers, or via a simple dictionary definition. But NPR doesn’t want to call a plagiarized convention speech a plagiarized convention speech. Why? Because there could be a controversy about it! As indeed there immediately was after Melania Trump’s plagiarized speech. Trump defender Chris Christie rejected that description. So did campaign chair Paul Manafort, who even blamed Hillary Clinton for the controversy.

NPR’s intention in these charged moments is not to describe the world vividly and accurately for listeners, but to escape from acts of judgment that could be criticized in the heat of a campaign. And even though it’s a fairly simple matter to assess what happened here and decide that, yep, the speech was plagiarized — and then report on whodunit — for NPR the relevant factor isn’t the ease of applying a standard definition of plagiarism but how simple it is to avoid getting dragged into a messy fight. And so the guidance went out: “It’s fine to say there’s a ‘plagiarism issue’ or that the speech last night raised questions about whether some parts were plagiarized…”

Alongside the production of news, NPR is worried about reproducing its own innocence in matters of controversy. The code for this is: people can make up their own minds. Which is really saying: NPR can’t think, but we invite you to!

9. Now we come to the most revealing moment in the exchanges I reproduced for you: when Sarah McCammon tells Clay Shirky: NPR’s guidelines are different than many academic institutions, which understandably may have a lower threshold. Fascinating! For it’s really the opposite. NYU, Harvard, Oxford all have a tougher standard than NPR. If you borrow someone’s words without attribution, that’s plagiarism and you have to face the consequences. Under the more relaxed standard that NPR favors, you not only have to borrow someone else’s words without attribution to be committing plagiarism, you also have to show malicious intent. And NPR has to have some reliable way of knowing your intent. This is a lower threshold. Because of it many more people will be able to commit plagiarism without being called out for it by NPR.

And yet reporter Sarah McCammon says NPR has a higher threshold. What does she mean? Well, she’s not an idiot. Her claim makes sense, but only if you understand the culture of timidity at NPR. What her bosses are worried about is making a judgment that could be contested. Before they’re willing to do that, they need a lot of evidence. What they have in mind is not “what’s the right thing to call this?” or “what’s the best descriptor for our listeners?” but “how can we make fewer calls that can be criticized by powerful actors?” and “how can we report on controversies without becoming part of them?”

When those are the starting points, a “lower” threshold means you are willing to make more calls that could be criticized. And academics can tell you: almost every student who plagiarizes says “it was not my intent!” If you’re going to be real about plagiarism, you are going to be criticized, not only by students but by their parents. If you have high standards, you take the heat. If you have low standards, you worry about how much heat you will get. Sarah McCammon had flipped this in her mind, and she was unaware of it. But she was right about one thing: it’s unproductive to rage at her, for she has no choice but to follow NPR guidelines.

10. If “academic institutions have a lower threshold” was the most telling thing she said, this was to me the most interesting:

.@Shoq @jayrosen_nyu Tell me this: if I just decide to declare it plagiarism, what exactly does that accomplish?

— Sarah McCammon NPR (@sarahmccammon) July 20, 2016

In a way she’s right. If she calls it plagiarism on air that doesn’t change anything. But that’s because calling things by their right names should not be an issue we have to fight with journalists about. The fact that it is an issue, not only with plagiarism but with more serious descriptors like torture, is a sign of weakness in the culture of journalism, and this is especially so at NPR.

This makes a lot of its listeners sad.

UPDATE, July 26: Steve Buttry wrote about this issue at his blog. He also got Mark Memmott, NPR’s editor for standards and practices, to comment. Here is what Memmott said by way of explanation:

When we wrote our Ethics Handbook in 2012 we included this definition of plagiarism: ‘Taking someone else’s work and intentionally presenting it as if it is your own.’ We realized that wasn’t a strict ‘dictionary definition.’ But we included the word ‘intentionally’ for a very specific reason: to allow us to apply some judgment.

We were thinking about how we would react if a journalist who had never stolen from someone else’s work inadvertently left a line or phrase from another file in his or her copy. Did that person make a serious mistake? Yes. Does that person deserve to be labeled a ‘plagiarist’ and be disciplined or even fired? We wanted some flexibility to make an intelligent decision.

On the morning when I reminded the staff about our definition, the story about Melania Trump’s speech was developing. I was thinking that we should not rush to hold her to a different standard than we would hold ourselves.

You and others have said that no one will ever admit they intended to plagiarize. You may be right. But I would say that a confession isn’t necessary to determine intent. It’s not hard to tell the difference between a slip by someone who’s never been accused or convicted of plagiarism and a story that’s got several “lifts” from different sources. And if someone slips and is later caught again, I think intent has been proven by his actions.

You wrote that we’re guilty of ‘comical gymnastics.’ That’s a good line. I would hope, though, that you would give us some credit for trying to think things through. Have we overthought it? Perhaps. But I would say our intentions are good.

One more thing. Sarah McCammon is a good journalist who was applying the guidance she was given by her editors. If there’s a problem, it’s because of her editors (most notably me), not her.