In which I give my opinion — an educated guess — about what I think happened, and call on GateHouse Media executives to level with us.

It’s been more than three weeks since Politico’s Ken Doctor, working off conversations he had with unidentified executives at the company, published this story: After Adelson: Gatehouse moves to repair Las Vegas damage. Since then, nothing has emerged to fill in the baffling unknowns that are so threatening to the company’s reputation. GateHouse Media executives seem to think they can skate on this, that the story will peter out, that we’ll forget what they have left hanging.

Will we? I hope not. That’s why I updated 19 times over six weeks my 11,000-word post on the mysteries surrounding the sale of the Las Vegas Review-Journal from GateHouse Media to the family of billionaire Sheldon Adelson. (Read it if you’re just coming to the story. I promise: the events there will amaze and amuse you.)

This I believe: To be a player in the news industry is to accept a business model that incorporates public trust. Without it, the assets you own aren’t worth as much. GateHouse Media owns 125 daily newspapers in the U.S., and some 500 smaller publications in 450 markets. It still operates the Review-Journal in Las Vegas (circulation around 165,000). By failing to address the very serious questions left hanging by the sale — many of which arise from the Review-Journal’s own reporting — the people who run GateHouse Media are, I believe, playing havoc with its reputation, which could eventually affect the value of the holding company, New Media Investment Group (NYSE: NEWM.)

But even if I am wrong about that: How can readers of the company’s news products who may be aware of the Adelson mess trust in what they are reading every day? How can journalists working for GateHouse have any confidence in company leadership if serious questions of institutional integrity go unaddressed? Why would editorial talent with options elsewhere stay or take a job there? When it’s impossible to trust in what it says about itself, what is a newspaper company worth, really?

Let’s go back to what Ken Doctor reported on Jan. 4. He said Gatehouse executives…

can be accurately described as “horrified” — thankfully and properly — by the many missteps involved in the Adelson sale. Company leadership’s first instinct was to hire a crisis management expert. Now it has come to realize that the problem of Las Vegas could more widely affect the view of the whole company.

Exactly so. Doctor did not mince words when he described what the problems were. They originate in this still-amazing story that appeared on the Review-Journal website Dec. 18: Judge in Adelson lawsuit subject to unusual scrutiny amid Review-Journal sale. (If you have not read it yet, what I have to say in this post won’t make as much sense, so please: click the link.) Doctor writes:

It appears that Adelson, or his people, tried to commandeer R-J investigative resources to “monitor” the performance of local judges who have been thorns in Adelson’s backside. The casino magnate is involved in a civil suit. Among the allegations in that suit: his company is doing business with the Macau gambling mob.

So far, no hard evidence has surfaced of Adelson or his people directing the R-J’s news staff, but the nature, timing and oddness of the coverage (the Times’ two-word take: “ominous coincidence“) ordered from on-high leads to an inescapable conclusion: Even before the legal transfer of the paper had been inked, Adelson, with Gatehouse management help, had trampled traditional journalistic lines and convention, believing he could use journalists as a hit squad.

It appears, then, that someone thought they could use GateHouse journalists as a hit squad. Whether it was the Adelson forces demanding such, or Gatehouse executives trying to impress them, or something else, we don’t know. That’s one of the unanswered questions. Here are ten more:

* Why did the Adelson family overpay for the Review-Journal by almost triple its market value, in Ken Doctor’s estimate? (Doctor studies the economics of the news industry at his site, Newsonomics.)

* Why, starting on Dec. 10, did GateHouse and the Adelson family try to keep the purchaser of the Review-Journal secret by using a newly-incorporated shell company, News + Media Capital Group LLC, which was to be “managed” by a man named Michael Schroeder, an obscure publisher of community newspapers in Connecticut? (Link 1, Link 2.)

* Why did Schroeder tell the journalists at the Review-Journal not to worry about who bought the newspaper and to focus on their jobs instead? (Link.)

* Why in September of 2015 did Schroeder, according to this report in the Huffington Post, offer a Connecticut reporter who used to work for him $5,000 to write a piece about Nevada judicial decisions, and mention Adelson in explaining the gig?

* Why two months later did GateHouse management try to get its investigative team in Sarasota, Florida to dig into “a potentially big story regarding the court system and potential ethics violations” among judges in Nevada? (Link.)

* Why in explaining that event did a GateHouse VP later tell a Review-Journal reporter that “we were engaged to tackle an investigative story in Las Vegas with no knowledge of the prospective new buyer?” Engaged… by whom? (Link.)

* Why after Sarasota begged off on that assignment did GateHouse management turn to the Review-Journal and, over the objections of top editors there, order its journalists to monitor the behavior of three Nevada judges? These included District Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez, the same judge “whose current caseload includes Jacobs v. Sands, a long-running wrongful termination lawsuit filed against Adelson and his company, Las Vegas Sands Corp., by Steven Jacobs, who ran Sands’ operations in Macau.” (Link.)

* What happened to the 15,000 words of notes and diaries that the reporters in Las Vegas compiled in completing the judges assignment, since according to the Review-Journal none of it was ever published? Where did it all go? (Link.)

* Why did Michael Schroeder publish in his tiny Connecticut newspapers a bizarre, rambling and apparently plagiarized article on business courts that criticized Nevada judge Elizabeth Gonzalez, and why did he put a fake name (Edward Clarkin) on it?

* And finally: what relationship to each other do these events bear? There are too many common elements and common players for the dots not to connect somehow. So how do they connect?

That is the question I turn to now. In this portion of my post, I am deliberately engaging in speculation (based on what’s already been published) and offering you my opinion about what went down— again, based on what has already been reported. Just to be crystal clear about it: I am not saying I know what transpired. Rather, in the absence of any decent explanation from GateHouse executives or Michael Schroeder I believe we are entitled to hypothesize and fill in the gaps with explanations that are at least plausible.

Working with limited knowledge — because the people who know won’t talk — I may well guess wrong on some points. My remedy for this: whenever possible link to what has been reported in the press or publicly stated by key players and let readers devise explanations alternative to the ones I have offered. Don’t buy my hypotheses? Come up with your own! That’s what comment sections are for.

Before I begin with my hypotheses I have to point out: there are five men who know. Together they can shed light on all the questions I have listed as open. These five are Michael Schroeder, publisher and editor of the New Britain Herald and Bristol Press in Connecticut; Jason Taylor, publisher of the Review-Journal in Las Vegas; David Arkin, Senior Vice President of Content and Product Development, GateHouse Media; Kirk Davis, Chief Executive Officer, GateHouse Media; and Michael E. Reed, Chief Executive Officer, New Media Investment Group, holding company for GateHouse. These are the men who are trying to skate off the stage without telling us what happened. I don’t believe they should get away with that. Do you?

Hypotheses: My best guess at what happened.

1.) Strategic overpayment

My hypothesis: The Adelson family overpaid for the Review-Journal by a substantial amount because there was more to the deal than just the purchase of a publishing asset. GateHouse would be expected to keep the Adelson family’s ownership stake a secret, and cooperate in the judges project. The sellers got a fantastic price for the newspaper and what is probably a lucrative agreement to operate the property, which GateHouse identified as a promising new business model.

Fact: Citing sources close to the transaction, the Review-Journal reported Dec. 15 that Adelson had been one of several bidders for the newspaper when Stephens Media was selling it and other holdings. He did not succeed in that round.

Fact: When Michael Schroeder was introduced to the Review-Journal newsroom in early December, he said the new owners had been looking to buy the Review-Journal from GateHouse “for six to eight months.” (Link.)

GateHouse closed on its purchase of the paper in March 2015. By April-May-June it was already in talks to sell it to the Adelson family. That’s fast. My guess: after losing out in the bidding with Stephens, the Adelson forces developed an understanding of some kind with GateHouse officials that would later come into play via the shell company, the secrecy surrounding the sale, and the investigation of Nevada judges.

Fact: Stephens Media LLC, which sold the R-J to GateHouse, is a private company. It can sell to whomever it wants, and reject an offer if it doesn’t like the buyer, or the terms. GateHouse is part of a public company, New Media Investment Group. It cannot easily dismiss an offer for one of its properties that is far above the going rate. (This may help explain why the Adelson family didn’t purchase the property directly from Stephens. Certainly it could have outbid GateHouse.)

Fact: Using circulation figures as a proxy for asset value, Ken Doctor estimated that at the time of the March 2015 sale to GateHouse, the Review-Journal and smaller publications in Nevada that were part of the deal were worth about $52 million. He comments:

Nine months later, though, the R-J, and its associated holdings, have been bought for $140 million, or almost triple the likely March value. It is worth noting that in 2015, daily newspaper financial performance only worsened across the board, down in mid- to higher-single digits for many mid-sized or larger dailies, such as the R-J. Financially, then, its value may have declined.

In announcing the sale that was completed on Dec. 10, New Media said its gain on the transaction would be “an estimated 69%.” That’s not the number that would astound the ever-struggling newspaper industry: “New Media completed the sale of the Review-Journal and related publications to News + Media Capital Group LLC for $140 million, or 7.0x LTM pro-forma As Adjusted EBITDA.”

We haven’t seen 7X multiples (a price based on annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) among midsize and larger dailies since before the recession. Today’s average multiple – and the one paid by newly acquisitive companies like New Media Investments – runs 3-4X. That’s what financial buyers have paid in recent years. Strategic buyers may pay a little more, as Jeff Bezos did for the Washington Post, but few have paid the kind of money just disbursed for the financially struggling Review-Journal.

Seven times earnings (EBITDA) when industry standard is 3-4? Must be a reason for that. My guess: GateHouse was expected to do things newspaper companies normally do not do.

2.) Bias anyone can see.

My hypothesis: I believe the Adelson forces had convinced themselves that the judge in the wrongful termination suit filed against Las Vegas Sands Corporation and Sheldon Adelson was biased against them in the extreme. They thought the evidence for this was so clear, so obvious that most fair-minded people would come to that conclusion once the facts were properly set forth. They further believed that skeptical news coverage asking the right questions about the troublesome judge (right from their point-of-view) and digging into the pertinent facts (pertinent from their point of view) would simultaneously help in getting Elizabeth Gonzalez disqualified and meet professional standards for fair and objective news coverage, an appealing two-fer.

And so the understanding they came to with GateHouse officials was, in their minds, really nothing more than tipping off a professional news organization to a great story. However, they were aware that some people wouldn’t see it that way, so steps had to be taken to conceal the Adelson stake in the Review-Journal and its self-interest in critical news coverage of the judge. I think Michael Schroeder and GateHouse both cooperated in this as part of some understanding they had with the Adelson forces, which could have been tacit or explicit. Maybe it wasn’t “you do this, we’ll do that” but just an agreement to check out a promising story… and if there’s something there you can be sure our journalists will want to run with it.

Fact: The New York Times reported this on Jan. 2:

On Nov. 4, with Mr. Adelson already in talks to buy The Review-Journal, the Nevada Supreme Court rejected a request from Sands China to have Judge Gonzalez removed from overseeing the lawsuit. The company said that rulings and comments made by Judge Gonzalez in court reflected a bias against Mr. Adelson and Sands.

My italics. They tried to get her tossed from the case for being biased against them. But their initial attempt did not succeed.

Fact: Two days after that ruling, GateHouse management ordered the Review-Journal newsroom to begin “monitoring” three Nevada judges, one of which was Elizabeth Gonzalez. “The monitoring effort began in Las Vegas on Nov. 6 with a call from a top GateHouse Media executive to Review-Journal Publisher Jason Taylor,” the newspaper reported.

Fact: On Jan. 12 of this year, the Review-Journal reported this about the attorney for Adelson’s son-in-law skirmishing with the judge in the wrongful termination suit:

At Tuesday’s hearing, Kozlov argued that Gonzalez should recuse herself from ruling on matters related to news articles about her. The judge told Kozlov to file a motion if he thinks she should refrain from ruling on an issue.

Fact: On Jan. 19 of this year, the Review-Journal reported:

Las Vegas Sands Corp. is making a new attempt to remove District Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez from a wrongful termination case that has received widespread publicity.

The company cited “recent intensified media coverage of the lawsuit” as one of the “new grounds” for requesting the judge’s disqualification.

Notice how Sands Corp. is trying to disqualify Gonzalez by pointing to news coverage that turns her into a figure of controversy, then questioning whether she can remain impartial.

3.) Schroeder screws up.

My hypothesis: Michael Schroeder tried to fulfill his part of the deal but slipped up three times, and therefore was ousted. Schroeder, I believe, was supposed to serve as front man for the purchase of the Review-Journal, allowing the Adelson forces to conceal their interest in the property indefinitely. He was also supposed to help arrange for critical coverage of Judge Gonzalez in a way that could not be traced back to Las Vegas Sands Corp. or the Adelson family. At all these tasks he failed.

Fact: In September, according to investigative journalist Peter H. Stone, Schroeder offered $5,000 to freelance reporter Scott Whipple, who used to work for his Connecticut papers. It was an unusual assignment:

Schroeder called it a “project” looking at Nevada judges who were handling business cases and mentioned Adelson’s name. To get him up to speed, Whipple recalled, Schroeder gave him a 40-page dossier comprising court documents and some newspaper clips.

After mulling the idea for a few days, Whipple decided to pass since the assignment didn’t mesh with his reporting experience and sounded unorthodox.

Schroeder’s first mistake: by outlining the Nevada judges assignment to a freelancer, by mentioning Adelson’s name in connection with it but failing to persuade Whipple to take the job, he created a source who had critical information and suspicions that not everything was kosher with the project.

Fact: On Dec. 10 the Review-Journal reported this:

Schroeder said News + Media does not own his newspapers or any other publications. When asked, he would not disclose the company’s investors.

“They want you to focus on your jobs … don’t worry about who they are,” Schroeder said.

This was Schroeder’s second mistake: Telling journalists who are trained to be curious and aggressive “don’t worry about who they are.” This practically invites them to dig into it, which is exactly what the Review-Journal reporters did. Within a week they were revealing the Adelson family hand. That was not supposed to happen. (After journalists revealed who the real buyers were, the Adelson family said it had always intended to disclose its stake but didn’t want to distract from a Republican presidential debate to be held in Las Vegas Dec. 15. But if that was really the case all they had to do was delay the announcement until Dec. 16. They had kept the deal secret for 6-8 months; what’s one more week?)

Fact: On Dec. 1, Schroeder had published in one of his Connecticut newspapers a bizarre and badly botched article on business courts, part of which attempted to raise doubts about Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez of Nevada.

Schroeder’s third mistake: he had loaded this article with red flags for curious journalists, from the phony name, ‘Edward Clarkin,’ to the illogic of reporting on Nevada judges for readers in Connecticut, to passages lifted from elsewhere and people quoted who could not recall being interviewed. As Review-Journal columnist John L. Smith wrote, “To call the story ham-handed does a disservice to ham.”

When scrutinized, this article greatly increased interest in the story among journalists around the country. Eventually, Schroeder had to apologize for it. And he became such an embarrassment to everyone involved that he was dropped from his role as “manager” of the Review-Journal, a kind of owner’s rep.

But none of that explains why he published the ‘Edward Clarkin’ article and took such risks. My guess: as part of the deal that made him “manager,” he had promised the Adelson forces that he would help produce news coverage critical of Judge Gonzalez. He struck out with freelancer Scott Whipple. Then GateHouse struck out with its Sarasota team. The Review-Journal journalists ordered to “monitor” the judges pushed back with such ferocity that nothing was published there, either. The ‘Edward Clarkin’ article was an act of desperation and bore the signs of that.

4. GateHouse strains to cooperate.

My hypothesis: Top GateHouse officials agreed to things they could not explain to their own people, which prevented them from executing on their end. Like Michael Schroeder they tried to arrange for critical coverage of Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez in a way that could not be traced back to the Adelson empire. But it didn’t work because they couldn’t get the journalists in their employ excited about the investigation, or even to see what the point of it was. Like Schroeder they grew increasingly desperate. After the sale to the Adelson family was revealed, reporters from the Review-Journal and the rest of the press started asking difficult questions. GateHouse executives froze. Because they had no answers that would pass scrutiny, they started to say bizarre things.

Fact: As the Review-Journal reported in its blockbuster story Dec. 18, in early November, David Arkin, GateHouse Media’s Senior Vice President of Content and Product Development, tried to interest Bill Church, executive editor of the GateHouse-owned Sarasota Herald-Tribune, in what was described as a “big story regarding the court system and potential ethics violations.” The potential story was said to involve “campaign finances and how judges were ruling on certain cases.”

After talking to his staff, Church told Arkin they could not immediately help.

“Given what I knew at the time, I said no, we just didn’t have the resources, and there were too many questions that still needed to get resolved,” Church said.

One major concern, Church said, was why the Sarasota newspaper would be asked to help when GateHouse also owned the Review-Journal, a larger newspaper in Las Vegas.

Note that neither GateHouse nor Bill Church in Sarasota told the Review-Journal newsroom about this event.

Fact: Shortly after the failed attempt to entice Sarasota, GateHouse officials turned to the Review Journal newsroom: (Link.)

…three reporters at the newspaper received an unusual assignment passed down from the newspaper’s corporate management: Drop everything and spend two weeks monitoring all activity of three Clark County judges.

The reason for the assignment and its unprecedented nature was never explained.

One of the three judges observed was District Judge Elizabeth Gonzalez, whose current caseload includes Jacobs v. Sands, a long-running wrongful termination lawsuit filed against Adelson and his company…

Fact: Journalists at the Review-Journal had the assignment forced on them: (Link.)

An internal memo outlining the court initiative notes that each reporter was to “observe how engaged the judge is in the case, whether they’re prepared or not, if they favor one lawyer over another, whether they’re over- or under-worked — even whether they show up for work on time, or not.”

The memo, authored by Review-Journal Deputy Editor James G. Wright, notes the initiative was undertaken without explanation from GateHouse and over the objection of the newspaper’s management, and there was no expectation that anything would be published.

Fact: When Review-Journal reporter Eric Hartley tried to ask Senior VP David Arkin about the Sarasota contact and any connection between the judges assignment and the Adelson empire, Arkin refused to be interviewed and instead sent a prepared statement, saying the company had been:

engaged to tackle an investigative story in Las Vegas with no knowledge of the prospective new buyer. Because Las Vegas was relatively new to the company, we decided to approach our newsroom in Sarasota, Florida, a team that is known for tackling big investigative journalism… On the face of the situation, we had what appeared to be a great story we were capable of investigating, and I wanted our team to show its talent. From my point of view, it was nothing more. (Link.)

Fact: As questions mounted over GateHouse’s behavior, David Arkin refused to explain to his own company’s reporter what this “great story” was all about. Eric Hartley, who now works for the Virginian-Pilot in Norfolk (not a GateHouse property), told me via email:

I emailed David Arkin seven times between Dec. 19 and 25 asking him to call me to address all the questions not answered in his emailed statement, including who “engaged” him to “tackle” the Las Vegas story and what that story was supposed to be. I also repeatedly texted and called him asking for those answers. Aside from that Dec. 18 emailed statement, he never responded.

Fact: David Arkin’s bosses were even less helpful. From the Review-Journal’s Dec. 18 story:

Whether there was a link between the GateHouse-ordered court monitoring assignment, the critical article in New Britain and the sale of the R-J to the Adelson family remains unclear.

Michael Reed, CEO of New Media Investment Corp., the parent company of GateHouse Media, declined to comment when asked whether Adelson was involved in the court monitoring directive. He said the effort was part of a “multistate, multinewsroom” investigative effort initiated by GateHouse, but said he did not know who started it or how it was approved.

“I don’t know why you’re trying to create a story where there isn’t one,” Reed told an RJ reporter on Wednesday. “I would be focusing on the positive, not the negative.”

(My italics.) Notice how the company’s top guy did know about a “multistate, multinewsroom” investigation, but did not know where it came from, or who authorized it. And he declined all comment on whether Adelson was involved. Mark Fabiani, the fixer hired by the Adelsons to handle the national press attention that has come to this story, has twice declined to answer that question when the New York Times put it to him. (Like, Arkin he wouldn’t even call the reporter back.) What does that tell you?

It tells me that truthful answers are too toxic, and deceptive ones stand a risk of being exposed by other parties. But again, that’s my opinion, not something I know for certain. One more thing: Arkin claimed GateHouse had “no knowledge of the prospective new buyer” in November of 2015. But Michael Schroeder told the Review-Journal newsroom the deal had been in the works since the spring of 2015! Arkin’s statement would be appear to be dead on arrival. To me these are signs of desperation.

What happens if we put all my hypotheses together? We get an educated guess — which is only my opinion — of what went down here.

The Adelson family overpaid by double or triple because there was more to the deal than the transfer of publishing assets. The shell company and Michael Schroeder were supposed to provide an extra layer of insulation.

Properly steered, skeptical journalists asking the right questions about the troublesome judge would simultaneously help in getting Elizabeth Gonzalez disqualified and meet professional standards for honest, hard-hitting news coverage. This made the arrangement seem almost… innocent.

In their minds the Adelson forces were simply alerting a newspaper company to a great story. But they also knew that some people, biased against billionaires, would not see it that way. So steps had to be taken to obscure the Adelson empire’s stake in the Review-Journal and its keen interest in critical news coverage of the judge.

Michael Schroeder and GateHouse agreed to take those steps. The understanding they had with the purchasers could have been tacit, explicit or some winking combination of both. Or maybe they all deceived each other. But Schroeder bungled his assignments, and GateHouse couldn’t deliver on critical coverage of Judge Gonzalez without provoking an open revolt from its journalists. The infamous ‘Edward Clarkin’ article was an act of desperation. Schroeder’s clownish appearance in the R-J newsroom became an invitation to skeptical journalists: start digging!

The sale to the Adelson family was not supposed to become public when it did. Journalists in Vegas weren’t supposed to connect the dots between the dubious story tip in Sarasota, the monitor-these-judges assignment forced on the Review-Journal ![mysteryman]() and some bizarre article on business courts published in a tiny Connecticut newspaper. But that connection was made — journalism! — and reporters started asking uncomfortable questions. “Who is Edward Clarkin?” added an element of mystery, a pop culture (parking garage) trope that greatly increased interest in the story.

and some bizarre article on business courts published in a tiny Connecticut newspaper. But that connection was made — journalism! — and reporters started asking uncomfortable questions. “Who is Edward Clarkin?” added an element of mystery, a pop culture (parking garage) trope that greatly increased interest in the story.

At the top of the company panic set in. Because they had no answers that would pass scrutiny, participants began to say things that made no sense. Or they stopped talking altogether.

How did the judges assignment get started? Who authorized it? Mike Reed, the company’s top executive, claimed not to know. In this he sounds radically incurious. When asked whether Adelson was involved at all, Reed flatly refused to answer. That’s damning. Mark Fabiani, the fixer hired by the Adelsons to handle national press attention, twice declined to answer the same question. That’ll fix it!

My guess: truthful replies were too damaging, further deception too risky. This is why nothing has happened since Ken Doctor wrote on Jan. 4 that “the company owes its readers, its own journalists and the wider public a series of explanations.”

Five men know. One of them, the hapless Michael Schroeder, has already apologized to his readers without really explaining anything. I doubt we will get much more out of him. Sheldon Adelson won’t even admit that he owns the Review-Journal, which is comical because his fixer puts him in the same category as Jeff Bezos and John Henry, two billionaires who do admit that they own newspapers. So I don’t think we’re going to get much from Adelson, either.

It is the reputation of GateHouse Media and the people who run New Media Investment Group that is truly on the line here. In my view Jason Taylor, David Arkin, Kirk Davis, and Michael Reed have reached a moment of truth in their careers. It is time for them to do what Ken Doctor said they must do: “publish a public accounting of the December mess.” And if they want to correct my informed guesswork — for that is what I have offered in this post — all the better. ![]()

After Matter: Notes, Reactions & Links

My thanks to Joseph M. Finnerty of Barclay Damon for his assistance in the preparation of this post and to John Robinson of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill for his comments and suggestions on an earlier draft.

UPDATE, Jan. 28. The noose tightens. News from Las Vegas. Jason Taylor, publisher of the Review-Journal, is out. (He’s one of the five men who know, as I put it.) Taylor was replaced today by Craig Moon, former publisher of USA Today, who left that job 2009. At the R-J Thursday morning there was an all-hands meeting where Moon was introduced. According to what I learned from GateHouse employees and this AP report, Jason Taylor will stay with GateHouse in an executive capacity overseeing Western properties. New publisher Craig Moon will not be a GateHouse person, as Jason Taylor was, but an employee in the House of Adelson.

“It wasn’t immediately clear what prompted the change in leadership,” the New York Times wrote.

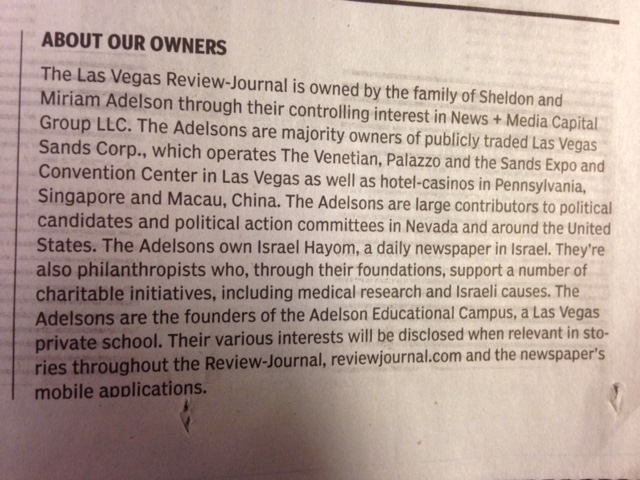

This development changes the executive picture, and indicates tightening control over the Review-Journal by the Adelson forces. Meanwhile, at the centralized print production center in Austin, GateHouse employees were told by Senior VP David Arkin that as of March 1 they will no longer be composing the pages of the Review-Journal. So the “divorce” between GateHouse and the Adelsons is being finalized. Also, from sources in the Review-Journal newsroom: the disclosure statement that used to run on page 3 of the print edition and the home page of the digital edition is no more, on orders of the new publisher:

![disclosure]()

It seems like the noose is tightening in the Review-Journal newsroom. Another indication of that: I’m told that at the all-hands meeting in Las Vegas to introduce the new publisher, no one even asked about the events of December and whether lingering questions around the judges investigation would ever be addressed. On the surface all is sunny however: This passage ran in the Review-Journal:

Moon said Sheldon Adelson asks insightful questions about newspapers. Adelson owns Israel Hayom, an Israeli newspaper.

“Sheldon is pretty articulate about things about newspapers, like: ‘So do you think the presses are being optimized?'” Moon said.

Moon said the owner puts the newspaper in a solid position for the future.

“I really do want to make this a world-class media business — the best it can possibly be,” he said. “We’ve got a great owner. We’ve got the commitment of a great owner. We’re not a public company having to sit and talk about how our earnings were the for the last quarter, and I think we’re going to be able to do some really big things here.”

UPDATE: Jan. 29: Things are coming into focus now. The Review-Journal reports that Sheldon Adelson is trying to lure the NFL’s Oakland Raiders to Las Vegas by proposing to build an expensive new stadium, which is what it takes:

Casino giant Las Vegas Sands Corp. will lead a consortium of investors planning to build a $1 billion domed stadium on 42 acres near the University of Nevada, Las Vegas that would house the school’s football team — and possibly a National Football League franchise.

There are all kinds of ways that owning the largest newspaper in Nevada could be useful in trying to get a project like that done. For example, this from a Las Vegas Sands Corp spokesman: “Abboud said Las Vegas Sands may seek legislative approval for diversion of hotel room tax revenues that now support the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority to the project.” Adelson needs lots of people and public bodies to go along with his scheme if the stadium plan is to work. When you factor that in, owning the Review-Journal makes more sense.

That is exactly the theme of this column by Jon Ralston, the most prominent journalist in the state: Adelson begins to play with his new toy. It’s about aiding Adelson’s campaign for a new stadium through orchestrated coverage in the Review-Journal.

Columbia Journalism Review: Review-Journal backtracks on ownership disclosure.

John Robinson, former editor of the News & Record in Greensboro, NC, reflects on the form that I used for this post, and says journalists should do this kind of thing more often. State what is known, what remains unknown, “show your work,” and try to connect the dots.

In the deep background to this story: Daily Beast, July 6, 2015: Why Did ‘Frontline’ Kill Lowell Bergman’s Gambling Documentary? “Recriminations and accusations are flying after the PBS series shelved veteran reporter Lowell Bergman’s documentary about the gambling industry in Macau.”

From a successful writer of thrillers, formerly with the CIA:

Coda: Events since I published this post show the path that participants in the fiasco are taking to avoid responsibility for everything I wrote about. Soon the Adelson empire and GateHouse Media will be divorced from each other. No more operating agreements, no more entanglement. The Adelsons can say, “The investigation of the judges? That was Schroeder, that was GateHouse. We had nothing to do with it.” GateHouse can say: “We have nothing to do with the Las Vegas newspaper any longer. We’re moving on.” By going their separate ways, they allow culpability and unanswered questions to drop into the abyss between them. The journalists in Las Vegas are now wholly under the control of Adelson and the new publisher who was announced Jan 28. The journalists at GateHouse will feel no duty to expose the goings-on at a former property. Most likely, we will never find out what happened, unless the national press makes a continuing and big deal out of it. But with no new information to report, the chances of that happening are thin. So in all probability, the attempted misuse of journalists as a ‘hit squad’ will go unexplained and unexposed. That’s frustrating. If David Carr were still alive, I would be sending this note to him. Instead, I am publishing it. But I do not have much hope that it will make a difference. Chances are no one will pay. It appears they got away with it.